As more mainland staff target promotion over job-hops, firms are facing a new training challenge

Companies operating in mainland China obviously know the value of staff training, but in recent years they have often been reluctant to invest. Their doubts stemmed from the very real concern that ambitious employees would soon be highlighting their new skills and experiences in job interviews as they looked to jump into a new role with another organisation.

However, perceptions and priorities appear to be changing. As China’s rate of economic expansion visibly slows, employees are realising the advantages of building a career by ascending through the ranks in one company, rather than continually hopping around. As a result, employers are far more prepared to invest in targeted training programmes for staff at all levels, feeling more confident that they – and not someone else – will reap the benefits in terms of productivity and having qualified people ready to move up.

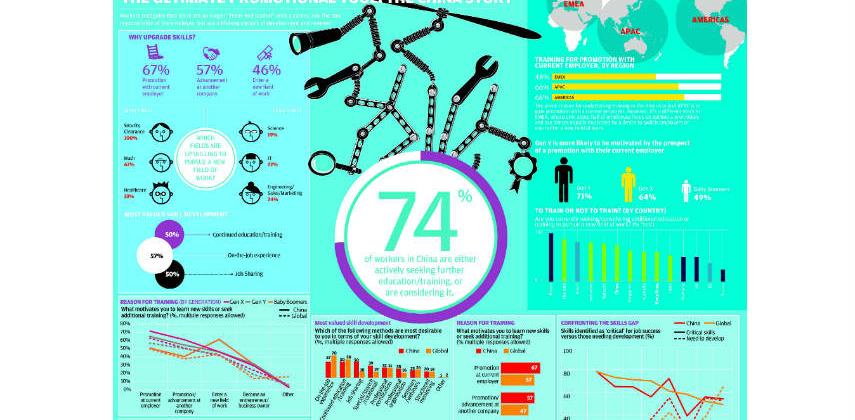

These trends are confirmed by findings from the latest Kelly Global Workforce Index, an annual survey which seeks feedback on workplace issues around the world. Specifically, it found that 67 per cent of respondents in China say that their main motivation for undertaking training is to improve their chances of a promotion with their current employer.

The survey also showed that China has become something of a skills “hotspot”, with 74 per cent of respondents actively seeking or considering some form of further education or training. This compares with 59 per cent reported for Europe and 55 per cent for the Americas.

“Employers are often uncertain about the merits of investing in training and professional development because they fear employees will simply take their new-found skills to a new organisation,” says Leroy Yue, managing director of Kelly Services China. “What this survey reveals is that most of those seeking to upgrade their skills are doing it so that they can advance in their existing roles.”

Implicit in this is a new realisation: sticking with an employer who invests in training may be the best way to remain relevant in a rapidly changing business environment. With less trepidation about losing good staff on the jobs merry-go-round, companies are also more willing to increase training budgets and rethink their policies and programmes accordingly.

“Decisions about training and professional development are now an integral part of the employment equation and have an important bearing on morale, performance and retention,” Yue says. “In addition, we see employees taking greater control over this aspect of their careers as they look at ways to renew and upgrade skills throughout their working lives.”

In identifying training priorities for mainland-based staff, Joean Wong, general manager for human resources in China at Swire Beverages, marks out the development of local leaders as essential. Such individuals are there to translate the corporate vision into action, get results on the ground and create new business opportunities. They need the full range of management skills, which run from decision-making and communications to effective team leadership and change management. They also need to understand the company, industry and competition.

All of that must be taught and tested in methodical fashion. Employers can’t just trust to luck or rely on hiring to fill critical vacancies.

“Executive coaching is being used to help leaders unlock their potential and climb the corporate ladder,” Wong says. “Overall, qualifications don’t seem to be the most important factor for promotion in China – except for finance and legal professionals. Instead, companies look at current performance, potential and the learning agility of staff, and will set up development plans to help [in-house] talent fill competency gaps between existing and target positions.”

To facilitate this, larger enterprises – particularly those with the support of an overseas network – are establishing their own academies, or “universities”, to give training initiatives the necessary structure and co-ordination. E-learning options are sometimes available, but, as a rule, mainland staff still tend to prefer classroom-style instruction and the interaction that goes with it.

As things evolve, younger staff are looking not just for on-the-job training, courses and workshops, but also overseas assignments which represent a fast track to wider experience and exposure.

“The motivation for most people is to enhance their abilities and improve promotion prospects with their present employer, rather than leaving to work somewhere different,” Wong says. “Seeing this – and wanting to retain top talent – more companies are now implementing mentorship programmes and corporate social responsibility activities, particularly targeted at younger employees. Such programmes are another way to build loyalty and enhance the sense of belonging.

“Of course, the real win-win situation is when the company can match the career plans and aspirations of an individual employee with the business development and succession plans of the organisation.”

As both an employer and a recruitment consultant for numerous enterprises, Cherol Cheuk, joint general manager for Hudson Shanghai, has been seeing increased investment in the teaching of hard and soft skills. While noting that expenditure on training is typically one of the first casualties when times get tough, she is nevertheless optimistic that companies and staff do now appreciate the interconnections between training, retention, career progression and prospects for long-term success.

“In Hong Kong, the group known as ‘young potentials’ are very much aware of the need for extra qualifications and are getting themselves prepared with certificates, courses and MBAs,” Cheuk says. “In China, we see more of that now, and it is better if companies lay down certain rules and requirements when they are ready.”

She adds that a corporate reputation for providing good training is a definite plus when it comes to attracting graduates or other recruits. In fact, that is one of the first items most candidates now ask about.

“Multinationals, in particular, want to make sure their organisation’s DNA exists in their China operations,” Cheuk says. “For this, they can’t just ‘borrow’ skills from elsewhere. They have to train accordingly.”

Career Advice

Featured stories and job trends

Select article category

Select article category

Career Advice Home

Personal Development and Career path

- Career Doctor

- Career Guidance and Counselling

- English for professional use

- How to Get Promoted

- Job seek in HK

- Plan and start the career path

- Tips to be more productive

- 職場英語 專家教路

How to successed in industry

- Banking and Finance

- Education and Training

- Government and NGO

- Property and Construction

- Startup

Industry Stories, recruitment tips and case study

- Featured stories and job trends

- Legal Case studies for employers

- Recruitment tips

- Successful entrepreneurs’ story

- Successful High flyers’ story

- 職業特搜

Job Market Report, fair and events

- Job fairs and Events

- Job Market Report

- Job Market Trend Report

Select article category

-

Select article category

- Career Doctor

- Career Guidance and Counselling

- English for professional use

- How to Get Promoted

- Job seek in HK

- Plan and start the career path

- Tips to be more productive

- 職場英語 專家教路

Career Advice Home

Personal Development and Career path

- Banking and Finance

- Education and Training

- Government and NGO

- Property and Construction

- Startup

How to successed in industry

- Featured stories and job trends

- Legal Case studies for employers

- Recruitment tips

- Successful entrepreneurs’ story

- Successful High flyers’ story

- 職業特搜

Industry Stories, recruitment tips and case study

- Job fairs and Events

- Job Market Report

- Job Market Trend Report

Job Market Report, fair and events

Skilling up, staying put

Mainland

,

Staff Training

,

Kelly Services

,

Employee Loyalty

,

Swire Beverages

,

Talent Retention

,

Hudson

,

Job Hopping

,

China

,

China Jobs

,

Mainland Jobs

,

Employment Market

,

Human Resources

Other Related Articles

Recommended jobs for you

- Job Posting Enquiry

- + 852 3619 9601 (M-F, 9am - 6pm)

- advertise@cpjobs.com

- General Enquiry

- + 852 3619 9600 (M-F, 9am - 6pm)

- info@cpjobs.com

- Partner with: Classified Post

- + 852 2565 8822 (M-F, 9am - 6pm)

- classified@scmp.com

Copyright © 2025. CPJobs International Limited. All rights reserved

Employment Agency Licence No. 76396