Despite this year's devastating earthquake in Japan, many firms have yet to develop human resources (HR) strategies to deal with such events.

A recent ECA International survey of 145 multinationals found that only 51 per cent had a formal disaster management programme in place. Meanwhile, 29 per cent of respondents said they were still developing a strategy, with 20 per cent saying they had no plans to develop any crisis policies at all.

Lee Quane, regional director for Asia at ECA International, attributes the inaction largely to a lack of experience and, in some cases, a need for flexibility.

"Some of the [unwilling] 20 per cent represents those with purely reactionary HR policies. They adjust or come out with guidelines if and when they're faced with a challenge," he says, adding that "the general thinking is, `if we haven't been affected, we don't need a policy'."

Firms that haven't been affected by crises are less inclined to enact response protocols. Oddly, so are those

"Looking at Hong Kong, for example, I don't think many people have changed their crisis management policy since Sars in 2003 - this despite the onset of subsequent epidemics in the past few years," Quane says.

Part of the timid response, he says, may stem from the perception that disasters are best dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

But while the need for a formal policy remains in question, Quane says there may be at least a few things that companies can and should do to prepare.

These include procedures such as monitoring the number of staff on assignments, be it for a short business trip, or a long-term placement.

Quane suggests compiling a list of contact details for employees and their next of kin, and having staff on long-term assignments register with a local embassy.

"In many cases, it's countries, not companies, who organise evacuations," he says. "If you're not on the embassy's list, then they won't inform you when an evacuation is taking place."

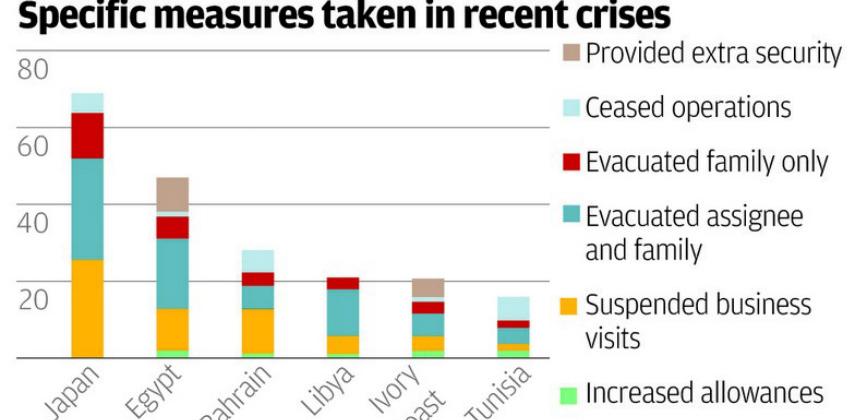

On insurance, Quane notes it's a matter of hit-and-miss, with some providers being more helpful than others. As for hardship allowances - financial rewards paid to employees to work in a different country - he says most firms are justifiably reluctant to adjust them, with just 4 per cent making such arrangements during the recent crisis in Egypt (see chart below).

"Paying somebody a few extra dollars to stay in a dangerous location may appease them, but it's not going to do much to keep them out of harm's way," he says. "This is the ultimate responsibility of a company - to protect you, to keep you safe."